Switching from a brand-name drug to a generic version seems simple-lower cost, same active ingredient, right? But for NTI drugs, that assumption can be dangerous. Narrow Therapeutic Index (NTI) drugs have a razor-thin line between helping you and harming you. A tiny change in blood levels-too little, or just a bit too much-can lead to treatment failure, serious side effects, or even death. And that’s why automatic generic switching for these medications isn’t just a policy debate; it’s a patient safety issue.

What Makes a Drug an NTI Drug?

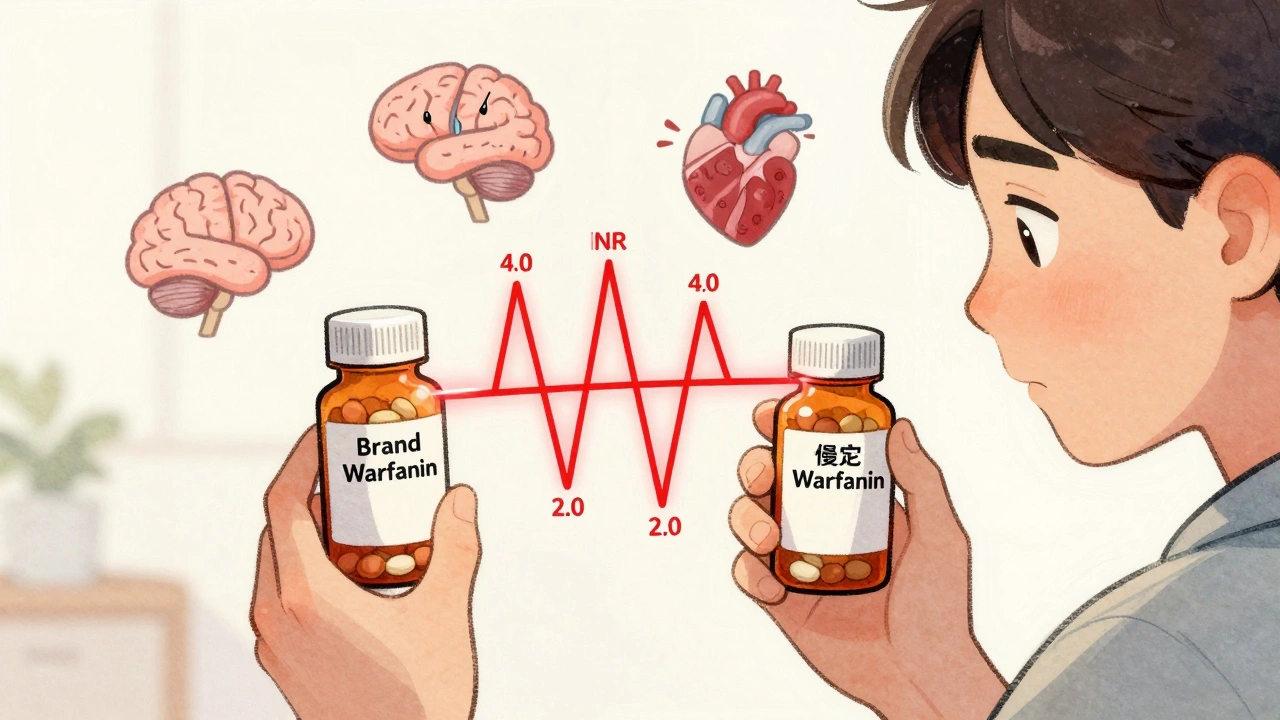

An NTI drug is defined by how close its effective dose is to its toxic dose. If the difference between the amount that works and the amount that causes harm is two times or less, it’s classified as narrow therapeutic index. For example, warfarin-a blood thinner-must keep your INR between 2.0 and 3.0. Go below 2.0, and you risk a stroke. Go above 3.0, and you could bleed internally. That’s a 50% margin for error. No other class of medication operates this close to the edge.

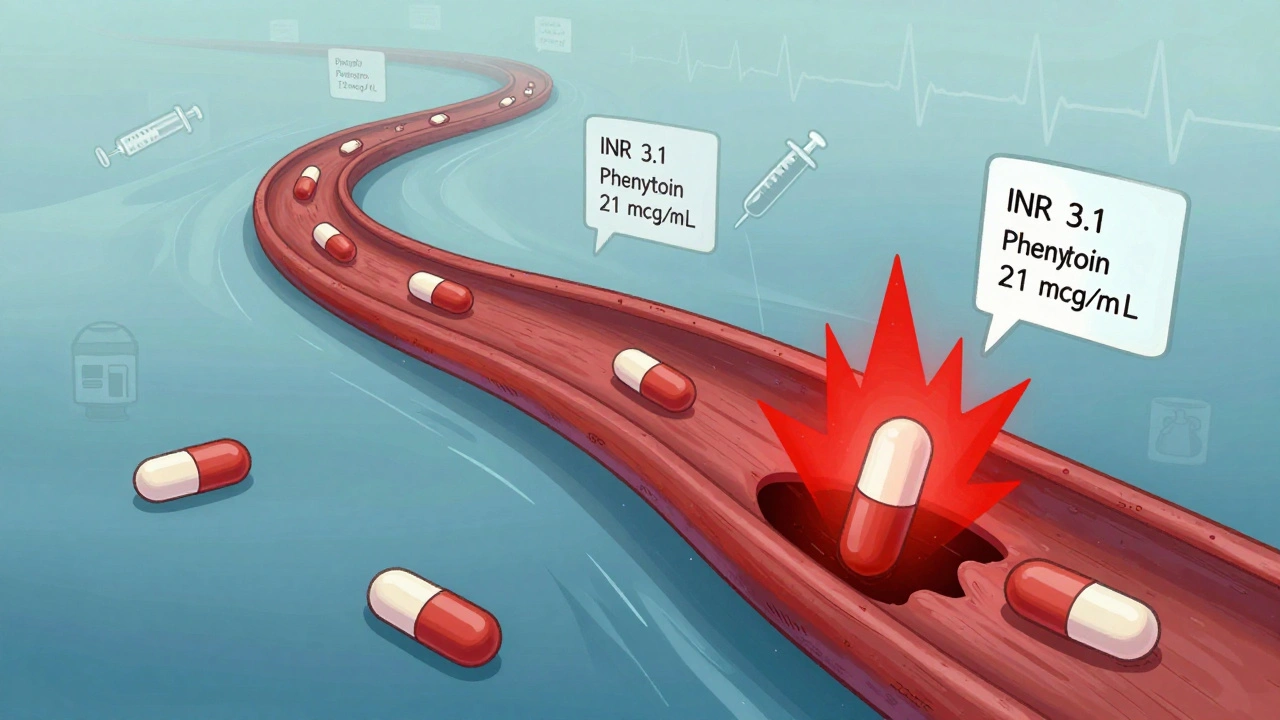

Other common NTI drugs include phenytoin (for seizures), lithium (for bipolar disorder), digoxin (for heart failure), and methadone (for pain and addiction). Phenytoin’s therapeutic range is 10-20 mcg/mL. At 21, you start seeing tremors and dizziness. At 30, you risk coma. There’s no room for guesswork.

Why Generic Bioequivalence Isn’t Enough

The FDA requires generic drugs to be bioequivalent to the brand version. That means the generic must deliver 80% to 125% of the active ingredient into your bloodstream compared to the original. Sounds fair-until you realize that 125% is a 45% swing above the target. For a drug like warfarin, that’s the difference between a safe dose and a life-threatening one.

Here’s the math: If your brand-name warfarin keeps your INR at 2.5, and you switch to a generic that delivers 125% of the same dose, your INR could jump to 3.1. That’s outside the safe zone. Now you’re at risk of bleeding. On the flip side, if the generic delivers only 80%, your INR could drop to 2.0 or lower. That’s a clot waiting to happen.

It’s not theoretical. In the 1980s, patients on phenytoin had breakthrough seizures after switching to generics. In one case, a man with controlled epilepsy had a seizure within days of switching. His blood levels dropped by 30%. He wasn’t noncompliant. He didn’t miss a dose. The generic just didn’t absorb the same way.

Real Cases, Real Consequences

Warfarin is the most studied NTI drug when it comes to switching. Some studies say generic warfarin is safe. Others show patients’ INR levels fluctuated wildly after switching-even when they were stable on brand-name Coumadin. One study found that after switching to a generic, 18% of patients had an INR above 4.0 within six weeks. That’s a bleeding risk. Another found patients needed more frequent blood tests and dose adjustments after switching.

For opioids like methadone, the stakes are even higher. In opioid-naïve patients, the difference between pain relief and respiratory depression can be as small as two-fold. If a generic version has slightly higher bioavailability, someone could stop breathing. If it’s lower, they’re left in pain. And because tolerance builds over time, the therapeutic window gets even narrower. A dose that was safe last month might be dangerous now.

Phenytoin patients report confusion, slurred speech, and loss of coordination after switching. Lithium patients have been hospitalized for toxicity after a simple generic switch. These aren’t rare outliers. They’re documented patterns.

The Regulatory Divide

The FDA says generic NTI drugs are therapeutically equivalent. But many doctors and pharmacists disagree. The American Medical Association has been clear since 2005: the prescribing physician should decide whether a substitution is safe-not the pharmacist, not the insurance company, not the pharmacy benefit manager.

Some states have taken action. North Carolina, for example, has a list of NTI drugs where automatic substitution is banned unless the prescriber specifically allows it. Other states require pharmacists to notify the prescriber before switching. But in many places, the default is still automatic substitution-unless the doctor writes “dispense as written” on the prescription.

The FDA itself admits the current 80-125% bioequivalence range may not be sufficient for NTI drugs. In 2010, an advisory committee said the standard was adequate. But in 2023, the agency began recommending tighter limits for certain NTI drugs. No official new standards have been set yet. So we’re stuck with rules designed for antibiotics and cholesterol pills, applied to life-or-death medications.

What Patients Need to Know

If you take an NTI drug, here’s what you must do:

- Know your medication. Is it on the NTI list? Warfarin, lithium, phenytoin, digoxin, theophylline, carbamazepine, and methadone are the most common.

- Ask your doctor if you’re on a brand or generic. Don’t assume.

- Never switch generics without talking to your prescriber. Even if both are labeled “generic,” different manufacturers can have different absorption profiles.

- Monitor your symptoms and lab results. If you’re on warfarin, track your INR. If you’re on phenytoin, ask for a blood level check after any switch.

- Keep a written list of every medication you take, including dosages and manufacturers. Bring it to every appointment.

Some patients are told, “It’s just a generic-it’s the same.” But with NTI drugs, that’s not true. The active ingredient is the same. The way your body absorbs it? Not always.

What Doctors and Pharmacists Should Do

Doctors need to stop treating NTI drugs like any other prescription. If you prescribe warfarin, phenytoin, or lithium, write “dispense as written” unless you’re comfortable managing the risks of a switch. Don’t rely on pharmacy systems to catch it. Be proactive.

Pharmacists should know which drugs are NTI in their state. If a patient is on lithium and a generic substitution is triggered, pause. Call the prescriber. Explain the risk. This isn’t about slowing down workflow-it’s about preventing ER visits and deaths.

Some pharmacies now maintain a list of NTI drugs and flag them automatically. That’s a good start. But awareness still isn’t universal. Many pharmacists don’t know the difference between bioequivalence and therapeutic equivalence. And that’s dangerous.

The Bottom Line

Generic drugs save billions. That’s a good thing. But cost savings shouldn’t come at the cost of patient safety. For NTI drugs, the margin for error is too small to gamble on interchangeability. The science, the case reports, and the expert consensus all point to one thing: NTI drugs need special handling.

There’s no reason we can’t have affordable generics for most medications. But for drugs where a 20% difference in absorption can kill, we need stricter standards, clearer rules, and more caution-not less.

Until then, if you’re on an NTI drug, don’t let a pharmacy decision become your next emergency. Ask questions. Stay informed. And never assume that “generic” means “identical.”

What drugs are considered narrow therapeutic index (NTI)?

Common NTI drugs include warfarin, phenytoin, lithium, digoxin, theophylline, carbamazepine, and methadone. These drugs have a very small window between the dose that works and the dose that causes harm. For example, phenytoin’s safe range is 10-20 mcg/mL-anything above 20 can cause toxicity like dizziness or seizures. Warfarin requires precise INR levels between 2.0 and 3.0. Even small changes in blood concentration can lead to serious outcomes like bleeding or clotting.

Can I switch from brand-name warfarin to a generic without risk?

Some patients switch safely, but many don’t. Studies show that switching from brand-name Coumadin to generic warfarin can cause INR levels to spike or drop unpredictably-even when all other factors stay the same. One study found that 18% of patients had an INR above 4.0 within six weeks of switching, putting them at high risk of bleeding. If you switch, your doctor should check your INR within 1-2 weeks and adjust your dose if needed. Never assume the generic will work the same way.

Why doesn’t the FDA require tighter bioequivalence standards for NTI drugs?

The FDA currently requires generics to be within 80-125% of the brand’s absorption rate, a standard designed for most medications. For NTI drugs, this range is too wide-some experts argue it should be 90-111% or tighter. The FDA has acknowledged this concern and recommended tighter limits for certain NTI drugs since 2010, but no universal new standards have been adopted. The delay is due to lack of consensus among regulators, manufacturers, and clinicians. Until then, the current rules remain in place.

Should my doctor always write “dispense as written” for NTI drugs?

Yes, if you’re on an NTI drug and your condition is stable, your doctor should write “dispense as written” on the prescription. This prevents the pharmacy from automatically substituting a generic version without your doctor’s approval. Even if you’ve been on a generic for years, switching to a different generic manufacturer can still change how your body absorbs the drug. The American Medical Association recommends that physicians, not pharmacists, make the final decision on substitution for NTI drugs.

What should I do if I’ve already switched to a generic NTI drug?

If you’ve switched, don’t panic-but do act. Contact your doctor and ask for a blood test or lab check (like INR for warfarin or serum level for phenytoin). Monitor for new symptoms-dizziness, confusion, unusual bleeding, seizures, or worsening pain. Keep a log of when you took your medication and any side effects. If anything feels off, get checked immediately. Many patients don’t realize their symptoms are linked to a recent switch. Your health isn’t worth the risk of waiting.

Juliet Morgan

December 6, 2025 AT 11:30I switched my mom from Coumadin to generic warfarin last year and she had a near-miss bleed. Her INR went to 4.8 out of nowhere. We didn’t even realize it was the switch until the ER doc asked if she’d changed meds. Don’t let anyone tell you it’s ‘the same.’ It’s not. I’m never letting that happen again.

Ada Maklagina

December 6, 2025 AT 21:54Been on lithium for 12 years. Switched generics once because insurance forced it. Ended up in the psych ward with tremors and confusion. Took three weeks to stabilize. Now I pay out of pocket. Worth every penny.

Harry Nguyen

December 7, 2025 AT 09:44So we’re supposed to trust Big Pharma’s brand-name markup over a generic that’s been approved by the FDA? Sounds like someone’s got a beef with capitalism, not pharmacology.

Mark Ziegenbein

December 8, 2025 AT 03:48Let’s be brutally honest here-the 80–125% bioequivalence window is a joke when applied to NTI drugs. It’s not just inadequate, it’s negligent. The FDA’s standards were designed for amoxicillin and atorvastatin, not for medications where a 15% variance in plasma concentration can induce a seizure or a cerebral hemorrhage. We’re applying a blunt instrument to neurosurgical precision. The fact that we still allow pharmacists to substitute without physician consent reveals a systemic devaluation of clinical nuance in favor of cost-cutting algorithms. And don’t get me started on how pharmacy benefit managers, who’ve never held a stethoscope, dictate treatment for patients with bipolar disorder or epilepsy. This isn’t healthcare-it’s actuarial math with a side of ethical bankruptcy.

Katie Allan

December 8, 2025 AT 17:24My dad was on phenytoin for decades. After switching generics, he started forgetting his own grandchildren’s names. We thought it was dementia. Turns out his blood level dropped 30%. He’s back on the original brand now. I wish someone had told us this before it almost destroyed our family.

James Moore

December 9, 2025 AT 13:37Oh, so now we’re treating NTI drugs like sacred relics? Let me guess-next we’ll be requiring handwritten prescriptions on parchment with wax seals? The FDA doesn’t approve generics lightly. If they say it’s bioequivalent, then it’s bioequivalent. People are just scared of change. And let’s be real-most of these ‘case reports’ are anecdotal noise from doctors who don’t understand pharmacokinetics. If your patient’s INR is unstable after a switch, maybe the problem isn’t the generic-it’s the dosing protocol. Or maybe your patient isn’t compliant. Don’t blame the system because you didn’t monitor properly.

Kylee Gregory

December 11, 2025 AT 01:51I think we’re all trying to balance two truths: generics save money and save lives in general, but NTI drugs demand more care. Maybe the answer isn’t banning substitution entirely, but creating a mandatory 14-day monitoring window after any switch, with automatic lab alerts triggered in EHRs. We have the tech. We just need the will.

Laura Saye

December 12, 2025 AT 14:59There’s a profound epistemological gap between bioequivalence and therapeutic equivalence. The former is a pharmacokinetic metric; the latter is a clinical outcome. We conflate them at our peril. For patients on methadone maintenance, even a 10% shift in Cmax can precipitate withdrawal or overdose-two outcomes that are diametrically opposed, yet both fall within the FDA’s ‘acceptable’ range. The regulatory framework is archaic. We need biomarker-driven substitution protocols, not population-based averages. Until then, we’re playing Russian roulette with polypharmacy.

Norene Fulwiler

December 13, 2025 AT 01:07My sister’s a pharmacist in Ohio. She told me they now have a pop-up alert in their system for NTI drugs-forces them to call the prescriber before substituting. It’s small, but it’s something. We need this everywhere.