QT Prolongation Calculator

QT Interval Calculator

Calculate corrected QT interval using Fridericia formula (QTc = QT / ∛RR) and assess risk of cardiac arrhythmias.

Note: Fridericia formula is recommended by major guidelines for accurate QT correction. For women, QTc > 470 ms or increase >60 ms is concerning. For men, QTc > 450 ms or increase >60 ms is concerning.

When you take an antibiotic like azithromycin or ciprofloxacin for a sinus infection or urinary tract infection, you’re probably not thinking about your heart. But for some people, especially older adults or those with other health conditions, these common drugs can quietly disrupt the heart’s electrical rhythm-leading to a dangerous condition called QT prolongation. This isn’t theoretical. It’s happening in hospitals and long-term care homes right now, and it can trigger a life-threatening arrhythmia called Torsades de Pointes. The good news? You can prevent it-with the right monitoring.

What QT Prolongation Actually Means

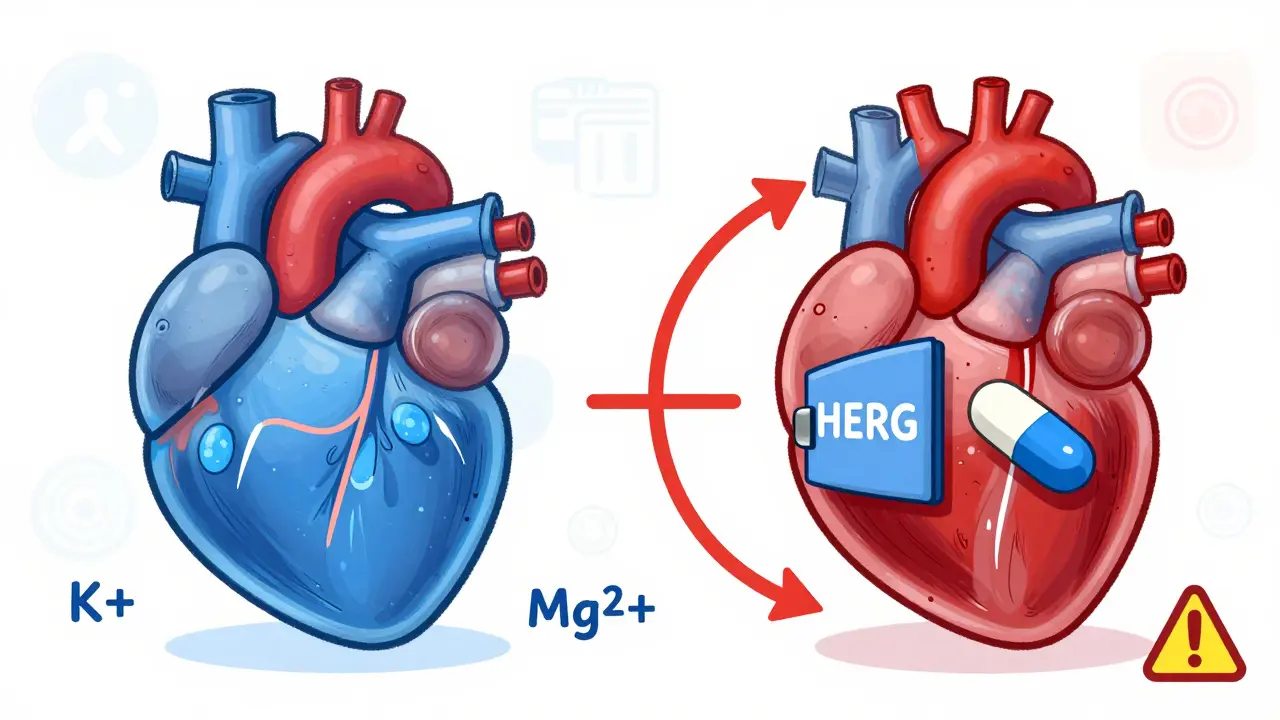

Your heart beats because of electrical signals. The QT interval on an ECG measures how long it takes for the lower chambers of your heart (the ventricles) to recharge after each beat. If that recharge time stretches too long-known as QT prolongation-the heart can misfire. That misfire might look like a skipped beat, or it might spiral into Torsades de Pointes, a chaotic rhythm that can cause sudden collapse or death if not treated immediately. Fluoroquinolones (like ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, moxifloxacin) and macrolides (like erythromycin, clarithromycin, azithromycin) are two of the most common antibiotic classes linked to this problem. They block a specific ion channel in heart cells called hERG. That’s the same channel targeted by antiarrhythmic drugs like sotalol. When these antibiotics block it, repolarization slows down. The result? A longer QT interval. It’s not the same for every drug. Moxifloxacin carries a higher risk than ciprofloxacin. Erythromycin is riskier than azithromycin. And levofloxacin? It’s often called low risk-but even that’s not zero. There are over 17 documented cases of levofloxacin causing Torsades de Pointes in the medical literature. So when someone says, “It’s just an antibiotic,” they’re missing the real danger: it’s not the drug itself-it’s the combination.Who’s at Highest Risk?

Not everyone who takes these antibiotics will have a problem. But certain people are walking into a minefield without knowing it.- Women over 65-especially those in long-term care homes. They’re three times more likely to develop Torsades than men.

- People with low potassium or magnesium levels. Even mild deficiencies make the heart more sensitive.

- Those already on other QT-prolonging drugs: antidepressants, antifungals, anti-nausea meds, or even some heart pills.

- Patients with heart disease-especially if their ejection fraction is below 40% or they have left ventricular hypertrophy.

- Anyone with a family history of long QT syndrome or sudden cardiac death.

- Critically ill patients in the ICU. They often have multiple risk factors at once: low electrolytes, kidney failure, sepsis, and multiple drugs.

How to Measure QT Correctly

You can’t just look at an ECG and guess. QT measurement is tricky. The standard method, Bazett’s formula, corrects for heart rate-but it’s flawed. At fast heart rates, it overcorrects. At slow ones, it undercorrects. That means a patient might be told their QT is normal when it’s actually dangerous. The better way? Use the Fridericia formula: QTc = QT / ∛RR. It’s more accurate, especially for predicting death risk within 30 days. That’s why the British Thoracic Society and other major guidelines now recommend it. If your hospital is still using Bazett’s, ask why. Also, don’t measure QT if the QRS complex is wider than 140 ms. That’s not true QT prolongation-it’s a conduction delay. Bundle branch blocks, pacemakers, or ventricular pacing can make the QT look longer than it really is. You need to interpret the ECG in context.

When to Check the ECG

Monitoring isn’t random. It’s timed. For macrolides, the British Thoracic Society says: get a baseline ECG before starting. Then, repeat it one month after starting treatment. If the QTc goes above 470 ms in women or 450 ms in men, stop the drug. That’s not a suggestion-it’s a requirement. For fluoroquinolones, the timeline is different. Check the ECG 7 to 15 days after starting. Then again at one month, two months, and three months. After that, periodic checks every few months are enough-if the patient is stable and has no new risk factors. Timing matters too. Peak drug levels happen about 2 hours after taking the pill. That’s when QT prolongation is most likely to show up. If you’re doing a hospital check, schedule the ECG for 2 hours after the dose. Don’t just grab it at random.What to Do When QT Prolongation Shows Up

If the QTc is over 500 ms-or if it increases by more than 60 ms from baseline-stop the antibiotic immediately. Don’t wait. Don’t reduce the dose. Stop it. Then, fix what you can. Check potassium and magnesium. If potassium is below 4.0 mmol/L or magnesium below 2.0 mg/dL, replace them. That alone can reduce arrhythmia risk by up to 70%. Don’t restart the same antibiotic. Even if you think “it was fine last time,” the next time might be the one that kills them. Switch to a lower-risk alternative. For UTIs, nitrofurantoin or fosfomycin are safer. For respiratory infections, consider doxycycline or amoxicillin instead of azithromycin. And document everything. Write down the exact QTc value, the formula used, the time of measurement, and the patient’s risk factors. If something goes wrong, that paper trail protects both the patient and the provider.

Why This Matters Beyond the Hospital

Most people think this is an ICU problem. But it’s not. It’s happening in outpatient clinics, urgent care centers, and long-term care homes. A 2021 study found that nearly 40% of ICU patients on ciprofloxacin and erythromycin developed QT prolongation within 24 hours. That’s not rare. That’s predictable. The FDA has issued multiple warnings about fluoroquinolones. They’ve restricted their use for simple infections like sinusitis or uncomplicated UTIs. But doctors still prescribe them. Why? Because they’re convenient. They’re broad-spectrum. They’re cheap. But convenience shouldn’t override safety. Especially when safer alternatives exist. The Canadian Network for Observational Drug Effect Studies (CNODES) is tracking real-world outcomes-and they’re seeing the same pattern: older women on multiple QT-prolonging drugs are ending up in the ER with cardiac arrest.Practical Checklist for Prescribers

- Before prescribing: Ask: Is this antibiotic truly necessary? Could a lower-risk drug work?

- Check for risk factors: Age? Gender? Electrolytes? Other meds? Heart disease?

- Get a baseline ECG: Especially if the patient is over 65, female, or on other QT-prolonging drugs.

- Use Fridericia formula: Don’t rely on Bazett’s.

- Monitor at key times: 7-15 days for fluoroquinolones; 1 month for macrolides.

- Stop immediately if QTc >500 ms or increases >60 ms from baseline.

- Replace electrolytes: Potassium >4.0, magnesium >2.0.

- Document everything: Measurement, formula, timing, actions taken.

What’s Next?

We’re moving toward smarter tools. Some hospitals are starting to use point-of-care apps that plug in age, gender, electrolytes, and meds to calculate individual QT risk. Genetic testing for long QT mutations is becoming more accessible too. But right now, the best tool is still the one you already have: a good ECG, a clear understanding of risk, and the discipline to follow the guidelines. Don’t wait for someone to collapse before you act. QT prolongation doesn’t announce itself. It creeps in quietly. But with the right checks, you can stop it before it’s too late.Can azithromycin cause QT prolongation?

Yes, but it’s lower risk than other macrolides like erythromycin or clarithromycin. Azithromycin still blocks the hERG channel, and cases of Torsades de Pointes have been reported, especially in patients with multiple risk factors like older age, low potassium, or other QT-prolonging drugs. It’s not safe to assume it’s risk-free.

Is ciprofloxacin safer than moxifloxacin for QT prolongation?

Yes. Ciprofloxacin carries a low risk of QT prolongation, while moxifloxacin is considered high risk. Moxifloxacin has been shown to prolong the QT interval more consistently and to a greater degree in clinical studies. For patients with any risk factors, ciprofloxacin is the preferred fluoroquinolone-if a fluoroquinolone must be used at all.

How often should ECGs be checked when taking levofloxacin?

For patients on levofloxacin, an ECG should be done 7 to 15 days after starting treatment, then again at one month, two months, and three months. After three months, periodic monitoring every few months is recommended if the patient remains on therapy and has ongoing risk factors. For low-risk patients with no history of QT issues or other risk factors, routine monitoring may not be needed unless new risk factors appear.

Can electrolyte imbalances make QT prolongation worse?

Absolutely. Low potassium (below 3.5 mmol/L) and low magnesium (below 1.7 mg/dL) dramatically increase the risk of Torsades de Pointes when combined with QT-prolonging antibiotics. Correcting these levels-targeting potassium above 4.0 mmol/L and magnesium above 2.0 mg/dL-can reduce arrhythmia risk by up to 70%. Always check electrolytes before and during treatment with these drugs.

Should I avoid fluoroquinolones for simple UTIs?

Yes, especially in older women with multiple health conditions. Guidelines from the FDA, CDC, and British Thoracic Society now recommend avoiding fluoroquinolones for uncomplicated UTIs because the risk of serious cardiac events outweighs the benefit. Safer alternatives like nitrofurantoin, fosfomycin, or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (if not allergic) are preferred. Fluoroquinolones should be reserved for complicated infections where no other options exist.

What’s the difference between Bazett’s and Fridericia formulas?

Bazett’s formula (QTc = QT / √RR) is older and commonly used, but it overcorrects at high heart rates and undercorrects at low ones. Fridericia’s formula (QTc = QT / ∛RR) is more accurate across a wider range of heart rates and better predicts 30-day and 1-year mortality. Major guidelines now recommend Fridericia as the standard for clinical decision-making, especially when managing QT prolongation risk.

Next steps: If you’re prescribing fluoroquinolones or macrolides, review your patient’s current meds and ECG history. If you’re a patient, ask your doctor: “Is this antibiotic necessary? Could it affect my heart? Have you checked my ECG?” Simple questions can save lives.

Nilesh Khedekar

January 16, 2026 AT 11:29Jami Reynolds

January 17, 2026 AT 16:34Crystel Ann

January 19, 2026 AT 11:58Nat Young

January 21, 2026 AT 08:48Niki Van den Bossche

January 21, 2026 AT 20:19Diane Hendriks

January 22, 2026 AT 01:47Dan Mack

January 22, 2026 AT 20:01Nicholas Urmaza

January 24, 2026 AT 01:15Sarah Mailloux

January 25, 2026 AT 10:59Amy Ehinger

January 25, 2026 AT 13:03RUTH DE OLIVEIRA ALVES

January 26, 2026 AT 11:25Jan Hess

January 26, 2026 AT 18:31