Levodopa Protein Calculator

How Protein Affects Your Medication

Protein can block levodopa's ability to reach your brain. Aim for less than 7 grams of protein per meal during waking hours to maintain optimal movement control. Your evening meal can have higher protein content.

Your Meal Protein Total

Your Daily Plan

According to the Protein Redistribution Diet:

- Breakfast & Lunch: Keep protein intake under 7g

- Dinner: You can have your highest protein meal

- Timing: Take levodopa 45 minutes before breakfast

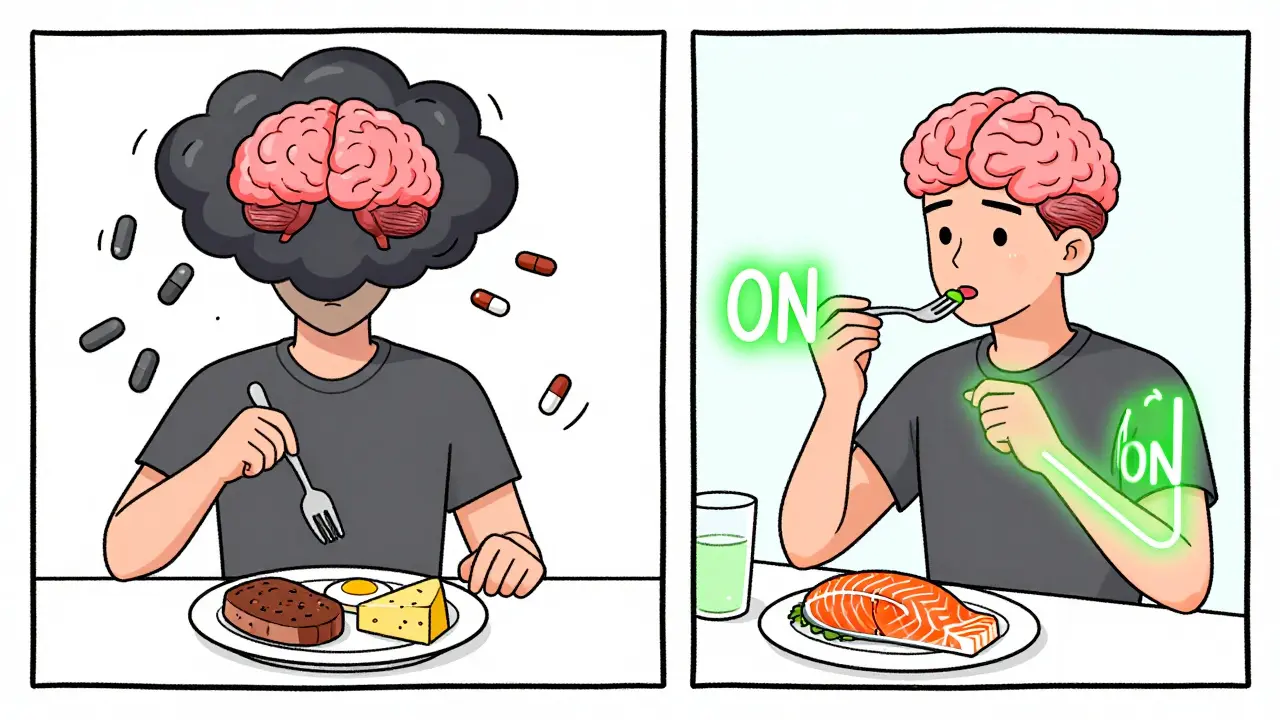

For people with Parkinson’s disease taking levodopa, what you eat can make a real difference in how well you move. It’s not just about timing your pills - it’s about what’s on your plate. A high-protein meal can turn a good day into a bad one, stealing away the mobility that levodopa is supposed to give you. This isn’t a myth or a rumor. It’s a well-studied, biological conflict happening inside your body every time you eat meat, eggs, beans, or dairy with your medication.

Why Protein Gets in the Way of Levodopa

Levodopa doesn’t just float through your body and slip into your brain. It needs help getting across the barrier that protects your brain - the blood-brain barrier. That help comes from a transport system called LAT1, which carries in large neutral amino acids (LNAAs) like leucine, isoleucine, phenylalanine, and tyrosine. These are the building blocks of protein. And here’s the problem: levodopa looks just like them. So when you eat a steak, a bowl of lentils, or a glass of milk, your gut releases a flood of these amino acids into your bloodstream. Suddenly, levodopa is stuck in line, waiting its turn. The result? Less of it gets into your brain. That means your tremors come back. Your stiffness returns. You feel like you’ve been thrown into an ‘off’ period - even though you took your pill.

Studies show that eating just 10 grams of protein with levodopa can cut absorption by 25%. A full high-protein meal - say, 35 grams or more - can delay how fast levodopa kicks in by over an hour. That’s not a small delay. For someone who’s already struggling with movement, it can mean the difference between walking to the kitchen and needing help to get up from the chair.

Who’s Really Affected?

Not everyone with Parkinson’s has this problem. About 40 to 50% of people on long-term levodopa start noticing it - usually after 8 to 13 years of treatment. That’s when motor fluctuations become common: the unpredictable swings between ‘on’ and ‘off’ states. It’s not about how much levodopa you take. It’s about how much protein is competing with it at the same time.

What makes it worse is that the brain’s ability to hold onto levodopa also declines over time. Even if some of it gets through, your brain can’t use it as efficiently. So the competition at the blood-brain barrier becomes even more critical. This isn’t something you can ignore if you’ve been on levodopa for years. It’s a key part of why your symptoms are changing.

Three Ways to Fight Back

You don’t have to give up protein forever. But you do need to change when and how you eat it. Three strategies have been tested and used in clinics for decades.

1. Protein Redistribution Diet (PRD)

This is the most effective approach. Instead of spreading protein evenly across meals, you eat almost all of it in the evening. That means breakfast and lunch are low-protein - think oatmeal with fruit, toast with jam, rice noodles, or a salad with olive oil. Dinner is where you get your chicken, fish, tofu, or beans. Why does this work? Because levodopa is usually taken three to four times a day, mostly during waking hours. By keeping protein low during the day, you give levodopa a clear path into your brain. Studies show this reduces ‘off’ time by nearly two hours a day and adds back about 30 minutes of smooth, controlled movement.

People who follow PRD closely report better control over their symptoms. One user on a Parkinson’s forum said, ‘I gained 2.5 hours of reliable mobility every day after switching to PRD.’ That’s life-changing.

2. Low Protein Diet (LPD)

This one is trickier. It means cutting total daily protein down to about 0.6 to 0.8 grams per kilogram of body weight. For a 70kg person, that’s around 45 to 55 grams a day - less than most people get in one meal. While this can help, it’s hard to sustain. Many people lose weight, get tired, or feel weak. In fact, 31% of those on strict low-protein diets lose more than 5% of their body weight in six months. That’s dangerous for older adults. It’s not a good long-term fix unless you’re carefully monitored by a dietitian.

3. Low-Protein Products

There are specialty foods now - low-protein bread, pasta, and even pizza crusts - designed for people with Parkinson’s. They help make PRD more doable. But here’s the catch: only 22% of users say they actually like them more. They’re expensive. They’re hard to find. And they don’t fix the core issue: you still need to plan your meals around timing.

Timing Matters - But It’s Not a Magic Bullet

Some doctors suggest taking levodopa 30 to 60 minutes before meals. It sounds simple. And for some people, it works. But it’s not reliable. If your stomach is slow to empty - common in Parkinson’s - the pill might sit there, waiting, while your food arrives. And if you take it too early, you might get nausea. Studies show this method helps only 30% to 65% of people. That’s not enough to rely on alone.

The best results come when timing is combined with protein redistribution. Take your morning pill 45 minutes before breakfast. Eat a low-protein meal. Then wait until dinner to have your steak or tofu. That’s the combo that works.

The Real Problem: Adherence

Here’s the hard truth: most people can’t stick to these diets. In one study, 68% of patients quit their protein-restricted plan within a year. Why? Social life. Family dinners. Holidays. The guilt of saying no to a slice of cake with whipped cream - or worse, a grilled salmon dinner with your grandkids.

And it’s not just about willpower. Many people don’t know how to plan these meals. They think ‘low protein’ means ‘no meat,’ but they still eat cheese, yogurt, nuts, and beans - all packed with amino acids. They don’t realize that a cup of lentils has 15 grams of protein. Or that two eggs have 12.

That’s why working with a dietitian is so important. People who get personalized meal plans - with recipes that match their culture and tastes - are 40% more likely to stick with it. A dietitian can help you swap out high-protein foods for low-protein versions, track your intake with apps like MyFitnessPal, and adjust your levodopa dose if needed.

What You Shouldn’t Do

Don’t cut protein entirely if you’re underweight or already losing weight. Protein isn’t the enemy - poor timing is. If your BMI is below 20, you need to focus on getting enough calories and nutrients. That might mean eating protein with your medication and accepting a little more stiffness - or adjusting your levodopa dose with your doctor’s help.

Don’t assume you’re fine just because you don’t feel worse after eating meat. The effects can be subtle. You might not notice you’re moving slower - until you try to get out of a chair or button your shirt. Keep a diary. Write down what you eat, when you take your meds, and how you feel. Look for patterns. You might be surprised.

What’s Next?

Researchers are working on smarter solutions. One new approach, called ‘protein pacing,’ is in clinical trials. Instead of eating all your protein at once, you spread it out in tiny amounts throughout the day - just enough to feed your muscles, but not enough to block levodopa. Early results show 68% of participants respond well, and adherence is much better than with traditional diets.

There’s also talk about new drugs that don’t rely on the LAT1 transporter at all. If they work, this whole problem might disappear. But for now, the best tool you have is knowledge - and a plan.

Practical Tips to Start Today

- Take your levodopa 45 minutes before breakfast - and make breakfast low-protein (fruit, toast, cereal, yogurt with low protein content).

- Use a food scale or app to track protein. Aim for under 7 grams per meal during the day.

- Save your biggest protein meals for dinner - after your last levodopa dose.

- Ask your doctor if your levodopa dose needs adjusting. You might need less if your protein intake is controlled.

- Don’t try to do this alone. Get help from a dietitian who knows Parkinson’s.

- Keep a symptom diary. Note when you feel ‘on’ and ‘off’ - and what you ate before each.

This isn’t about perfection. It’s about progress. Even small changes - like moving your chicken to dinner - can give you back hours of better movement each day. And in Parkinson’s, those hours matter.

Can I still eat meat if I’m on levodopa?

Yes, but timing matters. Eat meat and other high-protein foods during your evening meal, at least one hour after your last levodopa dose. Avoid protein during breakfast and lunch to give levodopa the best chance to work. A small amount of protein (under 7 grams) at meals won’t cause major issues for most people.

Does protein affect all Parkinson’s medications the same way?

No. Only levodopa is affected this way. Other Parkinson’s drugs like carbidopa, entacapone, dopamine agonists (like pramipexole or ropinirole), and MAO-B inhibitors (like selegiline) don’t compete with amino acids. If you’re on a combination therapy, protein mainly interferes with the levodopa part.

Why do some studies show no change in levodopa levels with high-protein meals?

That’s because the biggest problem isn’t always absorption in the gut - it’s transport across the blood-brain barrier. Even if levodopa reaches your bloodstream, the flood of amino acids from protein can block it from entering your brain. That’s why you still feel ‘off’ even if blood tests show normal levodopa levels.

How do I know if protein is affecting my symptoms?

Keep a daily log: write down what you eat, when you take your meds, and how your movement feels. Look for patterns - do you feel worse after lunch? Do you get stiff after eating eggs or beans? If you notice consistent ‘off’ periods after protein-rich meals, that’s a sign. Talk to your doctor or dietitian about testing a protein redistribution plan.

Is it safe to cut protein long-term?

Only if you’re monitored. Cutting protein too much can lead to muscle loss, weakness, and nutrient deficiencies - especially vitamin B12 and iron. If you’re underweight or over 70, you need more protein, not less. Work with a dietitian to find a balance that protects your movement without harming your health.

Can I use protein supplements to build muscle?

Avoid standard whey or casein protein powders - they’re packed with amino acids that block levodopa. If you need extra protein for muscle strength, talk to your dietitian about using low-protein alternatives or timing supplements only in the evening, well after your last levodopa dose. Some specialized supplements are designed for Parkinson’s patients, but they’re not widely available.

Marc Durocher

February 3, 2026 AT 13:40So let me get this straight - I gotta eat my steak at midnight just so I can walk to the fridge without falling over? Sounds like a sitcom written by a neurologist with a grudge.

But honestly? I tried it. Low-protein breakfasts? Oatmeal with banana and a splash of almond milk. I felt like a college kid again. And yeah, my ‘off’ time shrank by like 90 minutes. Not magic, but damn if it didn’t help.

My wife still makes fun of me for eating tofu scramble at 7 a.m., but she’s the one who now brings me coffee when I’m stuck on the couch. So… win?

Also, I’m not even gonna lie - I miss bacon. But I’d rather miss bacon than miss my grandkid’s soccer game.

larry keenan

February 3, 2026 AT 21:09The pharmacokinetic interaction between levodopa and large neutral amino acids (LNAAs) via the LAT1 transporter is a well-documented phenomenon, with robust clinical evidence supporting protein redistribution as a strategy to mitigate motor fluctuations.

Studies by Olanow et al. (2003) and subsequent meta-analyses confirm that plasma LNAA competition reduces cerebral levodopa uptake by up to 40% during high-protein ingestion. The temporal dissociation of protein intake from levodopa administration is therefore not merely anecdotal - it is pharmacologically necessary in patients with established motor complications.

However, nutritional adequacy must be preserved. The recommended daily protein intake for elderly adults with Parkinson’s remains 1.0–1.2 g/kg body weight, with redistribution rather than restriction being the preferred paradigm.

Consultation with a movement disorder dietitian is strongly advised to individualize regimens and avoid unintended catabolic states.

Gary Mitts

February 5, 2026 AT 13:47Just eat your meat after your last pill and stop acting like this is rocket science.

Also, tofu scramble is not food. It’s a cry for help.

clarissa sulio

February 5, 2026 AT 22:50My dad’s been on levodopa for 15 years and he still eats steak every night. Says he’d rather be stiff than eat ‘hippie food.’

He’s 78. He’s still driving. He’s still dancing with my mom at weddings.

Maybe the real problem isn’t the protein - it’s people trying to turn medicine into a diet cult.

Anthony Massirman

February 6, 2026 AT 10:39Bro, I tried the protein redistribution thing for 3 weeks. Lost 8 lbs. Felt like a ghost. My legs gave out during a walk.

My neuro said, ‘If you’re not gaining weight, you’re losing muscle - and muscle is your best friend right now.’

Now I take my meds 45 min before breakfast, eat low-protein until 6 p.m., then go nuts with chicken and eggs. No drama. No weight loss. Still get 4 solid hours of ‘on’ time.

Don’t starve yourself. Just time it right.

Bridget Molokomme

February 6, 2026 AT 19:19Wait - so I’ve been eating eggs and yogurt at breakfast thinking I was being ‘healthy’… and that’s why I’ve been stuck in the chair since 10 a.m.?

Oh my god. I feel like an idiot.

Also, I just Googled ‘low protein bread’ and it costs $12 a loaf. Like, what even is this world?

Monica Slypig

February 7, 2026 AT 22:39Ugh. Another ‘sciencey’ post from someone who clearly never met a real Parkinson’s patient. You know what helps more than protein timing? Real medicine. Real doctors. Not some blog with oatmeal recipes.

And why are we all pretending this isn’t just another ‘eat clean’ trend wrapped in neuro jargon? I’ve seen people lose 20 lbs trying this. That’s not progress. That’s a death sentence.

Becky M.

February 8, 2026 AT 07:52i’ve been doing prd for 6 months and it’s been life changing but also so hard to explain to family

my mom still brings me a cheese omelet every sunday and i just smile and say ‘thanks mom’ then eat it after my night pill

weirdly the hardest part isn’t the food - it’s the guilt. like i’m being rude when i say ‘no thanks’ to the chicken at thanksgiving

also - low protein pasta is a scam. it tastes like cardboard and costs more than my rent

but i can walk to the mailbox now. so… worth it?

jay patel

February 8, 2026 AT 09:15guys i live in india and we eat dal every day and i was terrified i had to stop but then my neurologist said its fine if i eat it after 7pm and i started using a food scale and now i know 1 cup dal is 18g protein so i just eat half and add more rice

also my wife makes this amazing low protein kheer with almond milk and cardamom and its like dessert and i dont feel like i’m missing out

and yes i still eat chicken but only at dinner and i time my meds 45 min before

also i use myfitnesspal now and its kinda addicting to see my protein numbers drop during the day

and no i dont drink protein shakes anymore because they are pure evil and block my meds like a wall

also my tremors are better and i can hold my grandaughter longer and that’s worth every bland breakfast

and yes i still miss idlis but i make them with less lentils now and it’s fine

and yes i still cry sometimes when i see people eating biryani and i can’t have it until 8pm but i’m alive and moving and that’s what matters

Ansley Mayson

February 10, 2026 AT 06:55So you’re telling me the solution is to eat less protein and time pills? Wow. Groundbreaking.

Meanwhile, the drug companies are still selling $12,000/year pills while we’re all scrambling to find low-protein bread.

Someone get me a real treatment. Not a meal plan.

phara don

February 10, 2026 AT 22:49Does anyone know if the new ‘protein pacing’ trial is still recruiting? I’m in the 68% who respond well to it and I’m desperate to get in before it ends. Also - has anyone tried combining it with timed caffeine? I read a paper that said caffeine might help with LAT1 competition… just wondering.

Hannah Gliane

February 11, 2026 AT 05:25Wow. You people are so obsessed with protein. 🤦♀️

My cousin has Parkinson’s and she eats whatever she wants. She’s 82. She’s still traveling. She’s still gardening.

Maybe the real issue isn’t your diet - it’s your mindset.

Stop trying to control everything. Just live. 🙄